After decades of hostility, a shared hatred of Iran – and a mutual

fondness for Trump – is bringing Israel’s secret links with Gulf

kingdoms out into the open. By Ian Black

In

mid-February 2019, Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister, flew

to Warsaw for a highly unusual conference. Under the auspices of the US

vice-president, Mike Pence, he met the foreign ministers of Saudi

Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and two other Gulf states that have no

diplomatic relations with Israel. The main item on the agenda was

containing Iran. No Palestinians were present. Most of the existing

links between Israel and the Gulf have been kept secret – but these

talks were not. In fact, Netanyahu’s office leaked a video of a closed session, embarrassing the Arab participants.

The meeting publicly showcased the remarkable fact that Israel,

as Netanyahu was so keen to advertise, is winning acceptance of a sort

from the wealthiest countries in the Arab world – even as the prospects

for resolving the longstanding Palestinian issue are at an all-time low.

This unprecedented rapprochement has been driven mainly by a shared

animosity towards Iran, and by the disruptive new policies of Donald

Trump.Hostility to Israel has been a defining feature of the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East since Israel’s creation in 1948 and the expulsion or flight of more than 700,000 Palestinians – which Arabs call the Nakba, or catastrophe – that accompanied it. Still, over the years, pan-Arab solidarity and boycotts of the “Zionist entity” have largely faded away. The last Arab-Israeli war was in 1973. Israel’s peace treaties with Egypt and Jordan are unpopular, but have lasted decades. The 1993 Oslo agreement between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) was an historic – if ultimately disappointing – achievement. And what is happening now with the Gulf states is a hugely important shift.

Evidence is mounting of increasingly close ties between Israel and five of the six members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) – none of which have formal relations with the Jewish state. Trump highlighted this accelerating change on his first foreign trip as president – to the Saudi capital Riyadh – by flying on directly afterwards to Tel Aviv. Hopes for Saudi help with his much-hyped “deal of the century” to end the Israel-Palestine conflict have faded since then. Yet Netanyahu is seeking to normalise relations with Saudi Arabia. And there has even been speculation about a public meeting between him and Mohammed bin Salman (MBS), the Saudi crown prince who was widely blamed for the brutal murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi last October. That would be a sensational – and highly controversial – moment, which is why Saudis are signalling frantically that it is not going to happen. Still, the meeting with Netanyahu in Warsaw went far beyond anything that has taken place before. The abnormal is becoming normal.

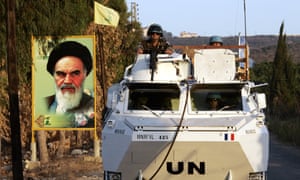

The original impetus for these developing relationships between Israel and the Gulf states was a mutual distaste for Barack Obama. In the early years of the Arab spring, he infuriated the Saudis and the UAE, and alarmed Israel, by abandoning Egypt’s president Hosni Mubarak, and then voiced support for the popular uprising in Syria and called for Bashar al-Assad to resign. In 2015, when the US-led nuclear agreement was signed with Iran, it was vehemently opposed by Israel and most Gulf states. That September, Russia’s military intervention in Syria marked the beginning of the end of the crisis for Assad. Tehran’s steadfast support for its ally in Damascus, and its backing of Hezbollah in Lebanon – Iran’s “axis of resistance” – was regarded with identical disgust in Jerusalem, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi.

“The Obama administration was hated by Saudi Arabia and Israel because it shunned them both,” a senior Saudi told me. A veteran Israeli official made the same argument: “There was a sense that we were looking at an American ’s administration that wasn’t as committed to America’s traditional friends. We had to make common cause because there was a sense of being left to fend for ourselves. Unwittingly, Obama contributed very significantly to the buildup of relations between us and the UAE and the Saudis.”

Netanyahu’s game plan is to promote relations with the Gulf and beyond, and thus to marginalise and pressure the Palestinians. “What is happening with Arab states has never happened in our history, even when we signed peace agreements,” is his carefully polished formula. “Cooperation in different ways and at different levels isn’t necessarily visible above the surface, but what is below the surface is far greater than at any other period.” As Dore Gold, Netanyahu’s former national security adviser, elaborated with a smile, these words are “very carefully drafted to give a positive message without spilling the beans.”

The priority for the Saudis and their allies is resisting Iran, which in the past few years has consolidated its position in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Yemen, where it backs the Houthi rebels. MBS notoriously described Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader, as a “new Hitler”. Netanyahu compared Obama’s nuclear deal to the Munich agreement of 1938 – and after Trump abandoned it last summer, Netanyahu signalled Israel’s readiness to join an “international coalition” against Tehran. “We were raised to see Israel as an enemy that occupied Arab countries,” argues an Emirati analyst. “The reality now is that the Israelis are there whether you like it or not. We have common interests with them – and it’s about Iran, about interests, not emotions.”

There is also a pragmatic recognition in Gulf capitals of the benefits of security, technological and economic links with an unassailably powerful Israel – not only for their own sake, but also because of the US approval that brings. Israel sees ties with the Gulf as an important way of demonstrating its own influence in Washington. “It is doubtful whether the scope of (US) aid to Arab countries could have been sustained without the support of Aipac (the main pro-Israel lobby group) and Jewish organisations,” suggests Eran Lerman, former deputy head of Israel’s National Security Council.

None of this means that the Palestinian issue has gone away. “Normalisation” (of relations with Israel) remains a dirty word for millions of Arabs, which is why autocratic Gulf leaders fear popular opposition to their new cosiness with Netanyahu. Formally, every GCC state remains committed to the Arab peace initiative of 2002, which offers recognition of Israel in return for a Palestinian state in the territories occupied in 1967, with East Jerusalem as its capital. But even this is far more than Netanyahu will ever accept: he will consider only a Palestinian “state-minus”, and openly refuses to dismantle the illegal settlements that divide the West Bank into disconnected enclaves. Netanyahu’s many Israeli critics – angry over the corruption charges he is facing as next month’s elections approach – have complained that he is exaggerating both the Iranian threat and the significance of his Gulf diplomacy, while completely ignoring the existential crisis in Israel’s own backyard – its ongoing failure to make peace with the Palestinians.

Netanyahu’s meeting with the Saudis and Emiratis in Warsaw was not the first dramatic public glimpse of this changing Middle Eastern reality. Last October, the Israeli prime minister held talks in Muscat, the capital of Oman, with its ruler, Sultan Qaboos bin Said. The following day, his Likud party colleague, the culture and sports minister Miri Regev, was visiting Abu Dhabi in the UAE, while at the same time Israeli athletes were competing in Doha in nearby Qatar.

News of Netanyahu’s Muscat trip included video footage of his talks in the ornate Bait al-Baraka palace. The prime minister, in a blue suit and tie, was seen exchanging pleasantries with the sultan, in a turban and traditional white dishdasha robe. The Israeli leader’s wife, Sara, was there with other members of his delegation, including an impassive middle-aged man called Yossi Cohen, head of the Mossad intelligence service.

During Regev’s stay in Abu Dhabi, where Israel’s top judo team was participating in a tournament, she wept on camera as Hatikvah, Israel’s national anthem (the Hebrew words are about yearning for Zion) was played. Later she toured the opulent Sheikh Zayed mosque, commemorating the UAE’s founder, a loyal supporter of the Palestinian cause. These two Israeli ministerial visits to Gulf capitals gave a powerful boost to the impression of dramatic changes in the region’s alliances.

But as news of Netanyahu’s visit to Oman emerged, there was a reminder of the risks of a backlash. Six Palestinians were killed and 180 injured by Israeli army snipers on the border of the Gaza Strip, where weekly protests now challenge the blockade imposed on the territory by Israel since 2007.

Netanyahu was not, in fact, the first Israeli leader to visit Muscat. The Labor prime minister Yitzhak Rabin met Qaboos in 1994, as did his successor Shimon Peres. But in the mid-1990s the Oslo peace process, albeit flawed and already stumbling, was still being pursued by Israel and Yasser Arafat’s Palestine Liberation Organization. It was still – just about – possible to believe in a happy end to the world’s most intractable conflict. Nowadays, by contrast, no peace talks have been held between Israel and the PLO since 2014, when the Obama administration finally threw in the towel. That is a very significant difference.

But in spite of these recent flashes of publicity, hard evidence of Israeli ties with the Gulf states is still rare – because they remain largely covert.

The links are most visible with the UAE, where Israel, uniquely, has an official diplomatic presence at the headquarters of the International Renewable Energy Agency in Abu Dhabi – though both countries emphasise that they do not have bilateral relations. Avi Gabbay, leader of the opposition Labor party, held talks there last December. Netanyahu is thought to have met Emirati leaders in Cyprus in 2015 to discuss how to tackle Iran. But secret contacts between the two countries were routine from the mid-1990s – some of which were recorded in the US diplomatic cables released by WikiLeaks. The Emiratis “believe in Israel’s role because of their perception of Israel’s close relationship with the US, but also due to their sense that they can count on Israel against Iran,” an Israeli diplomat noted in 2009, adding that in general Gulf Arabs “believe Israel can work magic”.

These “below-the-surface” relations suffered a grievous setback in 2010 when a Mossad hit team assassinated the Hamas operative Mahmoud al-Mabhouh in a Dubai hotel. Mabhouh was Hamas’s arms-procurement liaison with Iran. The Emiratis banned anyone identified as Israeli from entering the country, even if they were travelling on a foreign passport. But it wasn’t long before discreet diplomatic and business links resumed. “In such cases you simply keep your head down and wait until it all blows over,” said a Swiss-based Israeli businessman. In 2013 the Israeli president, Shimon Peres, spoke from Jerusalem via satellite to 29 foreign ministers from Arab and Muslim countries attending an Abu Dhabi conference.

The Israelis quietly participated in joint military exercises with UAE forces, both in the US and in Greece, from 2016. Last year UAE military personnel reportedly visited an Israeli airbase to review the operations of US-made F-35 fighter jets, though this was denied by Israel. Clandestine cooperation is believed to include Israeli intelligence surveillance of Iran, and the sale of Israeli drones used in the war in Yemen.

Qatar, the maverick of the peninsula, has long behaved more independently, and more so since a coalition that includes Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt imposed a blockade on Qatar in 2017, to pressure it over its support of Islamist groups and its perceived tolerance of Iran. But in the past few years Doha has played an increasingly public role in mediating between Israel and Hamas, which controls Gaza, with Qatar’s emissary delivering suitcases stuffed with millions of dollars in cash to pay official salaries and relieve the deepening humanitarian crisis in Gaza resulting from its blockade by Israel. Qatar is criticised by the Palestinian Authority, which controls the West Bank, for legitimising Hamas, its Islamist rival.

Oman also gets on badly with the Saudis and Emiratis because it has always had friendly relations with Iran, prompting speculation that Netanyahu’s trip was intended to send a message to Tehran. Omani sources believe, however, that the sultan’s invitation was about advertising his pro-Israel credentials to Washington, where Trump’s hawkish national security team is suspicious of Oman’s ties to the Islamic Republic. Iran’s foreign minister, Javad Zarif, revealed later that he had been warned in advance about Netanyahu’s trip and accused Israel of trying to cause rifts in the Gulf.

Fear of Iran, above all, is what has brought Israel and the Gulf states together. Suspicion of Tehran dates back to the 1979 Iranian revolution, but it has intensified in the past two decades. The US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 – which hugely increased Iran’s influence in the region by removing a longstanding enemy, Saddam Hussein’s Sunni-dominated regime – came a year after the exposure of a secret uranium enrichment facility revealed that Iran had not abandoned its nuclear ambitions. This sharpened the focus on the Islamic Republic’s regional aspirations, including a potential threat to Israel’s undeclared nuclear monopoly.

In 2004 King Abdullah of Jordan warned of the appearance of a “Shia crescent” stretching from Damascus to Tehran via Baghdad, where Iraq’s Shia majority had been empowered by the removal of Saddam. The assassination of the Lebanese prime minister Rafiq al-Hariri in 2005 implicated Syria and the Iranian-backed Shia organisation Hezbollah. In January 2006, Syria’s Bashar al-Assad met the hardline Iranian president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. In December 2005, at the summit of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation in Mecca, Ahmadinejad had used a speech to deny the Holocaust – described by one observer as “a brazen act of one-upmanship that left the Al Saud [Saudi Arabia’s ruling family] mortified and unable to respond”.

The key turning point was the 2006 war between Israel and Hezbollah. The 34-day conflict marked a step-change in regional dynamics. Riyadh condemned Hezbollah’s incursion into Israel and abduction of two Israeli soldiers, describing it not as “legitimate resistance” but a “miscalculated adventure”. The Saudis and Israelis had a “common interest in dealing Hezbollah and Iran a serious blow,” recalled Daniel Kurtzer, who had been US ambassador to Israel until the previous year. Officially sanctioned Saudi clerics excoriated Hezbollah, while opponents of Saudi Arabia’s rulers “seized upon the war to highlight the caution, immobility, impiety and – some cases, illegitimacy – of the Saudi regime,” as a later study concluded. In August, Assad insulted the rulers of Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Jordan as “half-men” because of their animosity to the Lebanese militia.

One of the key players on the Israeli side was the Mossad chief, Meir Dagan, who was credited with a proactive alliance-building strategy with Arab and other partners, in part as a means to enable Israel’s assassinations of Iranian scientists and sabotage of Tehran’s nuclear programme. “Israel and the Gulf states were in the same boat,” observed David Meidan, who ran Mossad’s international department.

“All of a sudden the Mossad was teaching Farsi,” a former intelligence official marvelled. It was reported around this time that a meeting had been convened in the Jordanian Red Sea resort of Aqaba between Dagan, Bandar and the head of Jordanian intelligence, who decided to “build up and accelerate intelligence exchanges” to cope with Iranian threats. The conspicuous presence of Dagan’s successor Yossi Cohen – nicknamed “the model” because of his fashionable suits – alongside Netanyahu in Muscat last October may have been intended to send a not-so-subtle signal to the Iranians about Israel’s intelligence access to Gulf capitals.

One former UAE diplomat told me that the threat from Iran today had a unifying effect comparable to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, which led to a previously unacceptable US military presence in Saudi Arabia. “If it wasn’t for the Palestinian issue,” the ex-diplomat said, “this relationship with Israel would be very public, and it would be very welcome, because we need their military equipment and technology.”

Jamal al-Suwaidi, the founder of the government-backed Emirates Centre for Strategic Studies and Research, put it more bluntly: “The Palestinian cause is no longer at the forefront of Arabs’ interests, as it used to be for long decades; it has sharply lost priority in light of the challenges, threats and problems that face countries of the region.” Similarly, he added, the question of Israel was not comparable to the “threats posed … by Iran, Hezbollah and terrorist groups”.

There is still audible dissent in the Gulf over the developing rapprochement with Israel. “I am against normalisation,” insists Abdulkhaleq Abdulla, a Dubai political scientist. “I am against dropping the Palestinian issue because others are capitalising on it politically. Although Palestine is not the number one issue, it is still an issue – in the heart maybe, not so much in the mind.” One indication, however, of UAE priorities can be found in the strict state controls imposed on media: news sites affiliated with Qatar and Iran are blocked, but Israeli websites are not.

In addition to shared contempt for Iran, the Gulf states and Israel have been brought together by a common hostility to Islamist parties. Arabic and English-language media associated with the Muslim Brotherhood, Turkey and Qatar routinely expose and lambast UAE links to Israel. Qatar-based al-Jazeera is an important source for these stories, as is the Middle East Eye website in London. Emiratis respond by recalling that the first ever Israeli mission in the Gulf was actually opened in Qatar, in the post-Oslo honeymoon of 1996. (Israeli representative offices in Qatar and Oman closed after the outbreak of the second intifada, or Palestinian uprising, in 2000, but discreet ties continued.)

Many important developments in the evolving relationship between Israel and the Gulf have gone unreported because they are masked by contradictory public positions – and sometimes by outright lies. In December 2008, when some 1,400 Palestinians were killed in Gaza in the Israeli military’s Operation Cast Lead, the Saudis publicly criticised Israel. Shortly afterwards, however, Riyadh appeared to acquiesce in further Israeli military action against Hamas, in the form of airstrikes against Iranian arms convoys in Sudan en route to Gaza. Leaked US cables showed the Israelis mounted a diplomatic campaign to stop weapons being delivered. When that failed, they launched long-distance raids across the Red Sea into Sudan in early 2009, but crucially gave prior notification to the Saudis, according to informed sources.

By then, according to the deputy head of Israel’s National Security Council, “senior professionals in the intelligence and security fields from Israel and the Gulf countries were collaborating”. The same sources confirm, as has been occasionally reported but always officially denied, that the Saudis agreed to turn a blind eye to Israeli air force flights across their territory in the event of an Israeli strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities, before the idea was abandoned because of Obama’s opposition in 2012.

Israeli trade with the Gulf states is currently estimated to be worth $1bn a year, though no official statistics are available on either side. The potential, however, is vast – in technology, especially cybersecurity, irrigation, medical supplies and the diamond industry, among others, it could be up to $25bn annually, according to a detailed new study.

Israeli businessmen using foreign passports fly regularly to the UAE, usually on commercial flights via Amman. “There is a huge amount going on,” says the Israeli representative of a multinational company who travels to Arab states with an EU passport.

AGT International, owned by Israeli Mati Kochavi, provided electronic fences and surveillance equipment worth $800m to protect UAE borders and oilfields. Emirati officials described this as a non-political decision motivated by national security interests. In 2014 Haaretz made headlines when it first spotted a mysterious weekly private flight from Tel Aviv, via Amman, to Dubai. Nowadays direct flights between the Gulf and Israel, though still unexplained publicly, are frequently reported on social media. Israeli businesses operate in the UAE via companies registered in Europe. Bills of lading are produced from an intermediary country, often Jordan or Cyprus.

Like the Emiratis, the Saudis have quietly engaged Israeli companies, especially in the security sphere. One Israeli firm was a subcontractor on the hi-tech barrier constructed from 2014 by the European defence giant EADS along the kingdom’s border with Iraq, a senior veteran of Israel’s defence establishment revealed in an interview.

In 2012, when hackers breached the computer system of Saudi Aramco, the national oil company, Israeli businesses were called in. Israel reportedly sold drones to Saudi Arabia via South Africa, but denied that it had sold its “Iron Dome” system to defend the kingdom from missile attacks by Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen. In 2018 Israeli media were allowed by military censors to report that the Israeli and Saudi chiefs of staff had met at a Washington conference for commanders of US-allied armies. The Saudis denied the story.

Unofficial Saudi spokesmen say cooperation with Israel is confined to the subjects of Iran and counter-terrorism – and complain that the Israelis exaggerate its extent for propaganda purposes. As one well connected Saudi journalist tweeted, with typical dismissiveness: “Fetishising non-existent collaboration between #Saudi/GCC states and #Israel has become a trend in western media/thinktank circles.” Foreign governments close to both countries believe the two maintain a hotline for emergencies and are in regular contact. “There is now contiguity between the Israelis and Saudis,” says a western intelligence source. “You have effectively the kind of security relations between countries that exist when they share a border. There are practical things that need to be sorted out, so you end up with a routine relationship which can create more senior contact and a more strategic outlook on both sides.”

It is a fairly open secret. In 2013, Bandar bin Sultan, by then running Saudi General Intelligence, met the then Mossad chief, Tamir Pardo, for what a senior British source described as a “long and boozy dinner” at a Knightsbridge hotel. “There has never been such active cooperation between the two countries, in terms of analysis, human intelligence and interception on Iran and movements loyal to it such as Hezbollah, the Houthis and the Iraqi Popular Mobilisation Units,” a specialist intelligence newsletter reported in 2016. Saudi officials were said to be as “pleased as punch”.

On the Saudi side, however, there are complaints that the relationship is an unequal one. Israel, it is said, has not always responded to requests for intelligence, even when submitted via the US. And there are indeed indications of an internal debate in Israel about the value of links with the kingdom. Its own sophisticated surveillance capabilities are not matched by what the Saudis have to offer, whether that’s knowledge of Yemeni tribes or Arabs in Iranian’s Khuzestan province, according to an Israeli with long experience of dealing with Riyadh.

There is also still a lack of trust between the two sides. “I can understand that the Israelis would not have given the Saudis sensitive information because they couldn’t be confident that the Saudis would have protected the source – and that would have created a serious counter-intelligence problem,” mused another intelligence veteran. “They are not natural partners. They have very different intelligence cultures. The Israelis are world-class and the Gulfies are not. The Israelis would not go into a relationship unless they get some proper dividend.”

The developing links between Israel and the Gulf were given a significant boost by Trump’s arrival in the White House – although early US plans for a meeting between Netanyahu, Saudi Arabia’s MBS and the Emirati crown prince, Mohammed bin Zayed, failed to materialise. But the trend was already clear under Obama. Signs of deepening Saudi-Israeli relations multiplied when King Salman came to the throne in 2015, and even more so since MBS – who was profiled by Israeli intelligence on Netanyahu’s orders – was promoted to crown prince.

In 2016 Israel gave the go-ahead to Egypt to transfer to Saudi Arabia the Red Sea islands of Tiran and Sanafir, at the mouth of the Gulf of Aqaba. A Saudi lobbyist, Salman Ansari, called for a “collaborative alliance” with Israel to help MBS’s Vision 2030 blueprint for economic reform and diversification. Both countries faced “constant threats from extremist groups … directly supported by the totalitarian government of Iran,” he argued. The $500bn Neom megacity project, near the borders of Jordan, Egypt and Israel, attracted strong Israeli interest. The Straits of Tiran, the blockade of which by Egypt’s PresidentGamal Abdel Nasser triggered the 1967 war, now faced a brighter future, reflected the commentator Abdelrahman al-Rashed, “one where peace and prosperity prevail”.

Trump’s inflammatory decision in December 2017 to move the US embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, breaching a long-standing international consensus, initially met with a muted response in Riyadh. The president’s “ultimate deal” to resolve the Israel-Palestine conflict was discussed by his son-in-law Jared Kushner with MBS. Subsequent leaks pointed to a key role for the Saudis in pressuring the Palestinians. And when the crown prince made a three-week trip to the US last spring, he transmitted even louder signals about his intentions toward Israel, telling the Atlantic that the Palestinians should accept Trump’s plan or “shut up and stop complaining” about an issue that was no longer a priority compared to confronting Iran. MBS also explicitly acknowledged Jewish claims to Israel, declaring: “I believe the Palestinians and the Israelis have the right to have their own land.” Palestinian demonstrators in Gaza burned pictures of the Saudi royals.

In the background, however were other signs of Saudi flexibility: in March 2018 a commercial flight from Delhi to Tel Aviv was allowed for the first time to cross Saudi airspace. But there was a significant qualification. “Kerry asked the Saudis to let [Israeli airline] El Al fly over their territory,” reflected an Israeli security expert. “And who got permission? Air India! it shows that the Saudis can be flexible but they cannot betray the Palestinians, not because they love them or trust them but because it is an issue for their people and the religious establishment – and also because of their position vis-a-vis Iran.” Nevertheless, it fitted the narrative that Netanyahu has been eagerly promoting, that relations with key Arab states were “improving beyond imagination” regardless of the Palestinian issue. In June the Saudi intelligence director Khalid bin Ali al-Humaidan reportedly joined Kushner and Trump’s envoy Jason Greenblatt, as well as the Mossad’s Yossi Cohen and his Palestinian Authority, Jordanian and Egyptian counterparts, in Aqaba to discuss regional security.

These increasingly cosy relationships suffered a serious blow with the murder of Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul in October 2018. Amid international condemnation and constantly changing Saudi responses, the Israeli government was initially silent. When Netanyahu eventually addressed the issue, he deplored a “horrendous” incident, but warned it was important that Saudi Arabia remain stable – which was more or less exactly what Trump said, too. Saudi sources said his position was “much appreciated” in Riyadh. Israel’s intelligence community was said to be alarmed by MBS’s recklessness. “Let’s hope that if he wants to assassinate people again – say commanders of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards – he’ll consult people with some relevant experience,” wrote the security expert Ronen Bergman. Surveillance equipment manufactured by the Israeli company NSO was allegedly used to track the Saudi journalist, according to the Washington Post. And one of the two top aides to MBS who were blamed for the killing was the most senior Saudi official to have visited Israel (in search of state-of-the-art surveillance technology), reported the Wall Street Journal. It revealed too that new arrangements had been put in place to allow Israel businessmen to quietly visit the kingdom.

In public, however, Saudi Arabia’s relationship with Israel remains cautious and reticent. Unlike the UAE, Bahrain and Qatar, it refuses to allow Israelis to attend international sports events. “Not hosting a chess tournament with Israeli participants is a statement of our resolution for a free Palestine,” commented the columnist Tariq al-Maeena. “As the Custodian of the two Holy Mosques, Saudi Arabia bears the weight of the Muslim world and this form of commitment is necessary to ward off grand Zionist designs for the region.” Last December the Saudis even opposed a UN resolution condemning Hamas, along with all other Arab states.

Among the Palestinian leadership in Ramallah, alarm seems to have subsided. Speculation about how far MBS will dare to go in embracing Israel is no more than “gossipy innuendo”, said the Palestinian ambassador in London, Husam Zomlot, who was thrown out of Washington as part of the US offensive against the PLO. Saeb Erekat, the PLO’s chief negotiator, scorned the “imperialist fantasies of the Trump team”, insisting that “the whole of Palestine remains close in the heart of every Arab – and is not going to fade away”.

Netanyahu is sticking to his script: visiting Chad in January, he boasted that Israel’s relations with that country had been renewed in the face of Iranian and Palestinian opposition, and that it was the result of improving links with the Arab world. But on the eve of the Warsaw conference, a leaked Israeli foreign ministry report assessed that the Saudis were not prepared to go further in developing overt relations. The same point was made by the Saudi Prince Turki al-Faisal, another ex-spymaster. “Israeli public opinion should not be deceived into believing that the Palestinian issue is a dead issue,” he said in an unprecedented interview with an Israeli TV channel.

The attitudes of Gulf governments have clearly changed. But the bottom line is that Israel has failed to provide the incentives required for the Saudis and their allies to come out of the closet, to allow them to reconcile geopolitical logic with popular sentiment, because it has not offered anything approaching an acceptable deal for the Palestinians. “Everyone knows about the rapprochement with Israel, but no one can talk about it publicly, and no one can advocate it because there is nothing for the Palestinians in return,” concludes an Arab analyst in Abu Dhabi. “The assumption is that if it was going to happen openly, it would have to be in return for something big, and it does not look as though that is going to happen.”

Many Israelis agree. Even the ex-Mossad director Pardo argues that the cosiest clandestine connections are no substitute for public engagement, reiterating that without significant concessions to the Palestinians, Israel’s relations with Arab states will continue to be limited, security-focused and largely secret. Netanyahu’s purpose, as another critic concluded after his Muscat trip, was to “prove that there was no basis to leftwing claims that the occupation and Israeli settlements hinder normalisation of ties with the Arab world”. The Palestinians, in other words, will simply not go away – whatever else happens.

Ian Black, former Guardian Middle East editor and diplomatic editor, is a visiting senior fellow at the Middle East Centre at LSE, who have just published his new report, Just Below the Surface: Israel, the Arab Gulf States and the Limits of Co-operation. His latest book, Enemies and Neighbours: Arabs and Jews in Palestine and Israel, 1917-2017, is out now in Penguin paperback and available at guardianbookshop.com

• Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, or sign up to the long read weekly email here.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire